In the British drama 'Sherlock,' Holmes demonstrates his ability to solve cases through brilliant deduction. However, his reasoning process is largely based on deduction and induction. Comparing this to the real world, Sherlock's approach, while dramatic, may not work well in reality.

This is because the deductions Sherlock uses rely on hypotheses designed for dramatic effect.

Let's take a robbery case as an example.

A window is broken, and a woman who has had her documents stolen is in a precarious financial situation. A common hypothesis that might arise at the scene is that 'someone broke into her house and stole her documents and ran away.'

However, based on the immediate observation that the broken glass is outside the window, Sherlock focuses on the hypothesis that the woman is the culprit, casting suspicion on her. This leads to her confession and confirmation of the truth.

However, in reality, this kind of leap in reasoning can be risky, as it requires direct verification of complex factors before it can be quickly revealed as true.

In the world of business consulting, this deductive and inductive reasoning is confirmed in the field of management science.

It is primarily suitable for improvement and scalability within a known domain. The logical development of McKinsey and BCG can be considered to align with this. A representative characteristic of deduction and induction is the presence of a hypothesis at the beginning. Based on a similar structure, the statistical assumption that such an approach is efficient emerges, leading to highly suitable results for the goal of achieving optimization within a complete structure.

And business growth involves repeated cycles of growth and crisis. While there are times when stable growth can be achieved through management, there are also times when attempts must be made to create something from nothing at the end of a period of growth.

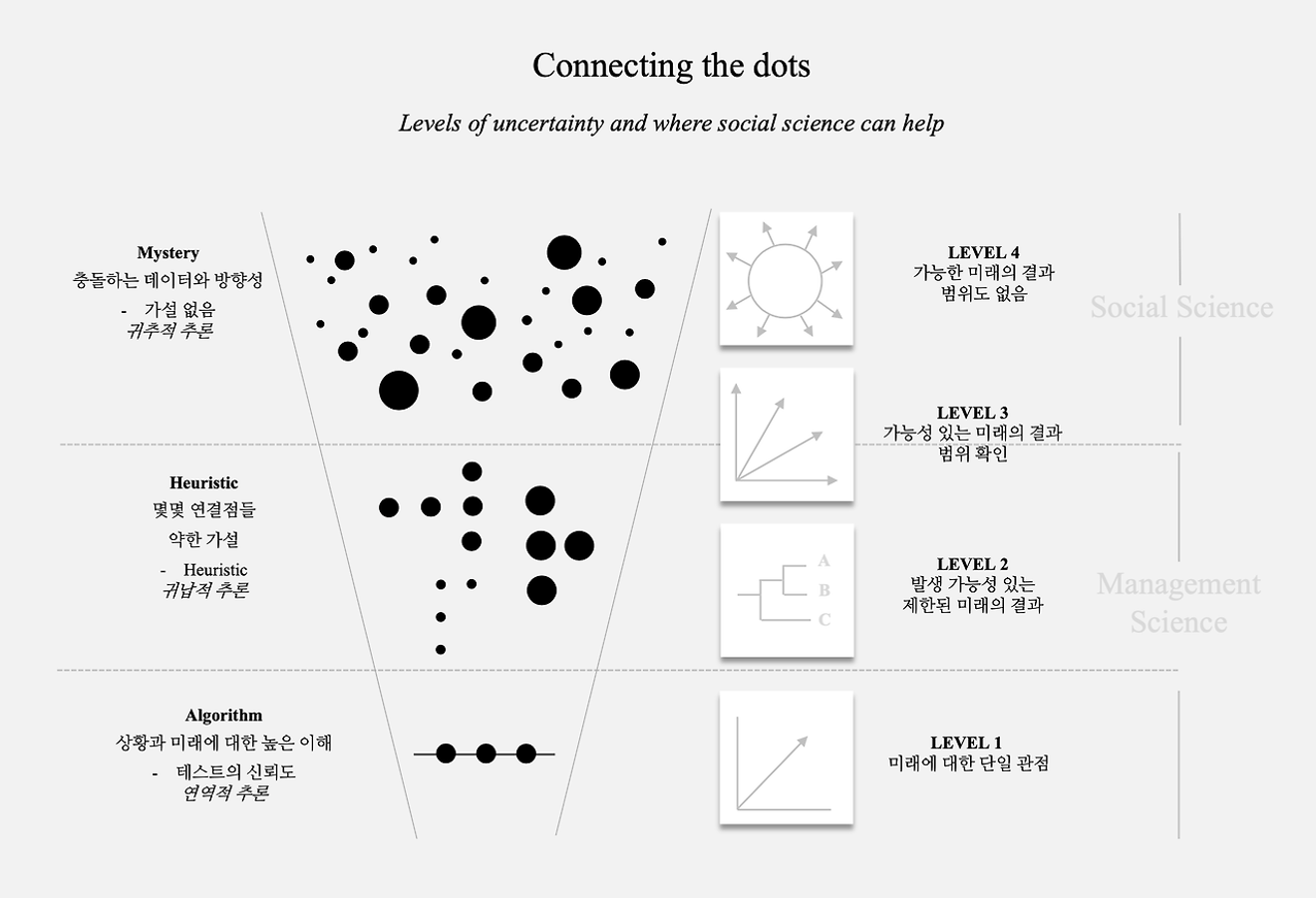

This challenge in new domains and markets implies investment in high uncertainty. When there are no hypotheses or when the reliability of hypotheses used in deductive and inductive reasoning is low, an abductive approach is appropriate.

The abductive approach begins by questioning familiar hypotheses.

When attempts based on previously accepted hypotheses are ineffective, and when facing challenges in new fields or markets with a lack of reliable background information, it starts by stepping into the real world. Then, based on the patterns observed and insights discovered within that real-world experience, new hypotheses are formulated, posing challenging questions to existing rules and creating a unique starting point.

This approach is suitable for exploration in unknown areas and is centered around originality. The logical development of ReD and Gemic, which are based on social science theories, can be seen as aligning with this.

It seems necessary for businesses to consider the level of uncertainty in the issues they face and to think about differentiating and applying various reasoning methods such as deduction, induction, and abduction.

This diagnostic framework helps identify big unknowns in business, a term that refers to unfamiliar and complex business problems where sensemaking can be especially useful. Here's an overview of the levels that categorize business problems and how sensemaking applies:

Level 1: Knowns

Characteristics: Familiar with the customers and market; clear problem definition; future outcomes can be predicted; conventional data and analytics can be used to address it.

Example: A sales issue during the holiday season can be traced to weather-related factors; increasing advertising and discounts can help resolve the problem.

Level 2: Hypotheticals

Characteristics: Moderate familiarity with the customers and market; a range of possible outcomes; similar problems seen before; hypotheses can be framed and tested; conventional data and analytical models may apply.

Example: Per-store sales are down despite increased investment in salespeople. A range of hypotheses can be tested to find the root cause.

Level 3: Big Unknowns

Characteristics: Highly unfamiliar with the customers and market; no clear sense of likely outcomes; problem not encountered before; no hypotheses to test; conventional data and analytics are unlikely to provide clear solutions.

Example: An innovation pipeline full of ideas, but product launches are not driving growth. In this case, sensemaking can help understand unfamiliar social or cultural contexts and guide new strategies.

Source: An Anthropologist Walks into a Bar…

Comments0