- Human Phenomena as the Basis for Business Decisions - 2

- This article introduces a phenomenon-centric approach that prioritizes human phenomena as the basis for business decision-making. Instead of focusing on megatrends, it offers a method for discovering new opportunities based on customer behavior and needs.

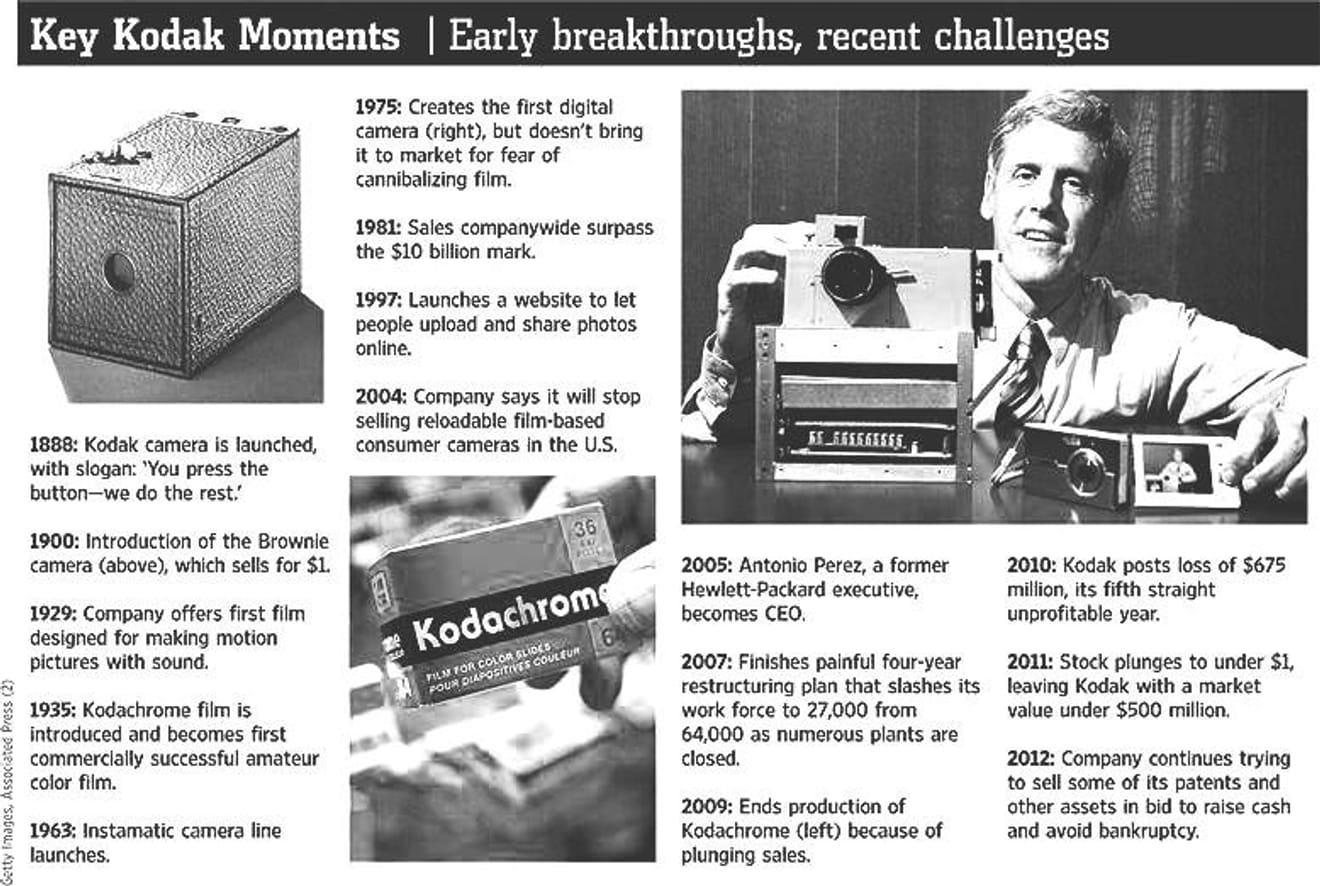

Kodak, the creator of the first digital camera, filed for bankruptcy in 2012.

That same year, Facebook acquired the photo-sharing platform Instagram for \$1 billion.

Kodak founder George Eastman believed in the \"democratization of photography,\" changing how people took pictures to make them accessible to everyone. While customer response was positive, the company's core revenue came not from cameras but from film and prints. Kodak maintained a razor-blade business model, selling products cheaply to then sell expensive consumables. Of course, Kodak invested in digital camera technology and understood that many people shared photos online. However, despite having opportunities over a decade, they failed to recognize that the online photo-sharing phenomenon was a new business, not merely an extension of their printing business.

-

Why Good Decisions Are Difficult: The Human Factor

One of the main reasons experienced executives within a company make poor decisions when trying to move to the next stage of their core business is the \"human factor.\" Social scientists and behavioral scientists have proven that humans are not the rational, calculating machines assumed in microeconomics. In this regard, here are five biases that executives experience as inherently human:

Status Quo Bias

- A tendency to prefer things to remain relatively the same.

We tend to leave things as they are for at least two reasons. The first is loss aversion, where we are more sensitive to the risk of loss than to the prospect of gain. The second is the sunk-cost fallacy, where we continue to invest even when the initial economic rationale is no longer valid, because too much has already been spent.

Bandwagon Effect

- A tendency to follow the actions or beliefs of others.

We tend to believe and act in the same way because many people believe and act that way. Worse than making a huge strategic mistake is being the only one in the industry making that mistake. When conviction and enthusiasm for a particular industry trend spreads, it's difficult to muster the courage to deviate, relying instead on your intuition, information, or analysis. The subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S., where many Wall Street banks simultaneously approved loans to those who lacked repayment ability, illustrates this point.

Confirmation Bias

- A tendency to filter information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions.

As humans, we tend to seek out opinions and facts that support our beliefs and hypotheses. This manifests in two ways: selective recall, the habit of remembering only the facts and experiences that reinforce our assumptions; and biased evaluation, the rapid acceptance of evidence that supports our hypothesis while applying stricter scrutiny to contradictory evidence.

Anchoring Effect

- A tendency to over-rely on one piece of information when making decisions.

We tend to rely too heavily on a few pieces of information when making decisions. For example, many fund managers advertise fund products based on past performance. However, the statistical correlation between past and future performance has not been shown in many studies. In other words, it's merely an approach to raising customer expectations of future good performance by citing past good performance.

Overconfidence Bias

- A tendency to overestimate one's own performance.

We often overestimate ourselves. In general, employees and companies overestimate their performance. Employees tend to overestimate their contributions, resulting in the sum of all contributions often exceeding the actual figures. Furthermore, people tend to be overconfident about their abilities. Surveys in relevant research found that up to 90% of people believed they were better drivers than the average driver.

These five common biases make it difficult for corporate executives to maintain a fact-based perspective. These biases lead to several key problems.

First, they underestimate the value of investments for new growth because they are already adept at identifying the risks of investment and the risk of failure. Second, executives strive to ignore the competitive advantage, leading them to pursue directions that do not lead to competitive differentiation. Finally, executives' preconceptions, coupled with a few attractive data points and their own demand for excessive accuracy, make it difficult to quickly change the direction of the business when necessary.

So how can companies overcome these very human biases to make better decisions? How could Kodak have seen the value of the opportunity they didn't want to see?

Due to character limits, please see the following link for the continuation.

Comments0